This is the second blog post in this series looking at the requirements that the State of Colorado and City of Denver adopted to implement building performance standards (Blog # 1 can be accessed here). It will review the benchmarking requirements that determine the scope of the building performance standard through “covered building” definitions that use building type and square footage as parameters. This blog will raise issues on whether and how the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) applies to these requirements.

Energy benchmarking is the cornerstone of these regulations to address the energy use and the consequent GHG emission of existing buildings. There is no prohibition to require benchmarking under the EPCA. The following describes the benchmarking requirements.

Energy Benchmarking and Covered Building Definitions

The State of Colorado Regulation 28 requires benchmarking of all “covered buildings” defined as buildings with gross floor space of 50,000 sq ft or more occupied by a single occupant or group of tenants. It expressly excludes:

- storage facilities;

- stand-alone parking garages;

- an airplane hangar that lacks heating and cooling;

- buildings with more than half of the gross floor space used for manufacturing, industrial, or agricultural purposes;

- or single-family homes, duplexes, or triplexes.

Notably, Data Centers have their own definition and compliance pathway because of the energy intensity of their operations and the difficulty in defining an EUI pathways for energy use reduction.

The City of Denver’s Ordinance requires benchmarking of “covered buildings” that are 25,000 sq. ft. or larger, significantly increasing the number of buildings required to benchmark relative to the overall state. Benchmarking is not required for buildings that:

- were not occupied and did not have a certificate of occupancy for all 12 months of the calendar year required for benchmarking;

- were not occupied because of renovations for all 12 months required for benchmarking;

- where a demolition permit has been issued and demolition commend on or before date of benchmarking reporting is required;

- are in qualifying financial distress (qualified tax lien sale/public auction, court appointed receivership, or acquired by deed in lieu of foreclosure); or

- used primary for manufacturing or agricultural processes (majority of energy consumed must be for this purpose).

There is nothing controversial or at risk under the EPCA specific to benchmarking. The application of building performance standards to existing buildings creates the greatest risk for EPCA preemption. Next, a discussion comparing the two approaches will raise the question of whether there is a distinction between whole building performance standards under the EPCA for existing buildings and whether there is a distinction between GHG regulations of existing buildings and energy efficiency regulations of existing buildings under the EPCA.

Building performance requirements are described next.

Building Performance: Energy Use Intensity (City of Denver) v. GHG Emission Reduction (State of Colorado)

The requirement for the State of Colorado sets two GHG reduction targets: 7% reduction by 2026 and 20% reduction by 2030. Regulation 28 creates two ways for compliance: meeting the building type EUI score by 2026 or 2030; or meeting the GHG intensity score for the building type by 2026 or 2030. It also creates four main pathways for compliance to provide significant flexibility to a building owner as well as providing several means of achieving compliance through adjustments if a building cannot reduce its GHG emissions below the threshold by the target date.

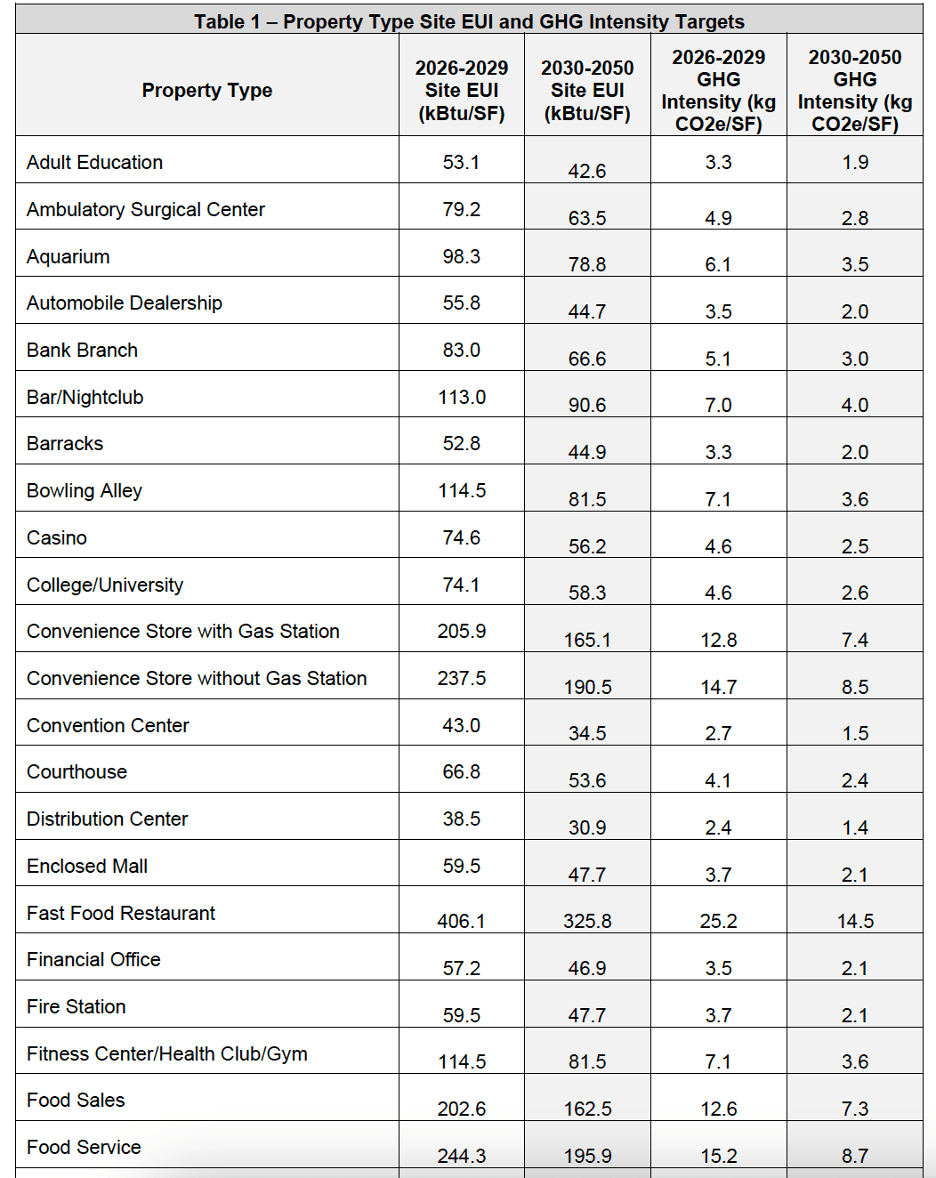

First, the building owner may meet the site EUI target by property type in Table 1 of Regulation 28. Below is a small screen shot capture of part of Table 1 that shows examples of the building type designations. Table 1 covers a total of ~55 building types:

Second, if unable to meet this EUI target, the building owner may choose a standard percentage energy reduction of 13% in comparison to the buildings 2021 benchmarked baseline EUI by 2026 and an energy reduction of 29% in comparison to the buildings 2021 benchmarked baseline EUI by 2030.

Third, alternatively, the building owner may choose GHG emission reductions to demonstrate compliance. This allows the use of customer-owned distributed generation, retail distributed generation, utility subscription services (e.g., solar gardens), or other approved alternatives. It requires a showing that all cost-effective energy efficiency and electrification measures have been exhausted before renewable energy offsets in the form of renewable energy credits (RECs) can be used.

Fourth, the building owner can choose to use a standard GHG percent reduction that has been converted to a GHG intensity value to demonstrate a 13% reduction compared to 2021 benchmarked baseline by 2026 and 29% reduction compared to 2021 benchmarked baseline by 2030. Additionally, Regulation 28 allows building owners to request adjustments to the compliance timeline, adjustment to the EUI of the standard performance requirement for 2026 and 2030, and the ability to request use of a performance standard for under-resourced buildings to achieve the 2026 or 2030 performance standards.

The State will issue a penalty of $2000 for the first violation and up to $5000 for each subsequent violation of the building performance standard. Additionally, the State will issue civil penalty of up to $500 for a first violation and up to $2,000 for each subsequent violation of the benchmarking requirement.

The amount of flexibility granted to meet the requirement and to seek timeline or performance standards adjustments is one of the ways that the State of Colorado likely will use to defend this regulation, but several questions remain. Is it enough that there is an option to use a federally approved covered product to comply but then also being required to take additional action and/or incur additional cost? Is there a distinction between the State of Colorado’s regulation of GHG emissions from existing buildings versus the City of Denver’s regulation of energy use for existing buildings? Does the regulation’s allowance for adjustments to timeline, EUI standard, or use of different standards if a building qualifies as an under-resourced building, while changing the burden, make any difference in terms of EPCA preemption? Will the court even reach these issues under an injunction analysis?

The answer to these questions will depend on how the district court interprets the words “concerning energy efficiency, energy use, ….”. It is possible that regulating whole building GHG emissions falls outside of this language if the court distinguishes between energy use of a covered product (e.g., quantity of energy consumed by an appliance) and the type of energy used (e.g., natural gas versus electric). Because the regulation applies to whole building energy use, it will need to distinguish between the applicability of EPCA preemption that only applies to covered products and all other related energy use and energy efficiency measures in buildings. Does “concerning” apply to entire buildings and consequent GHG emissions or only those of covered products? Where does EPCA preemption end?

For example, is it defensible to set a GHG emission standard that allows compliance with a U.S. DOE approved covered product that is electric but that prohibits the use of a natural gas U.S. DOE covered product, not because of its efficiency or the maximum quantity of energy used but because of the GHGs emissions of the source? Does Regulation 28 compliance require the electric, non-combusting covered appliance to exceed U.S. DOE energy efficiency or energy use standards in all case and for all buildings? If it is only for certain cases and certain buildings, does this justify preemption of the entire regulation? Does it matter if additional action or expense is required to use an electric covered product that does not exceed U.S. DOE energy efficiency or energy use standards when the regulation applies to a whole building that includes appliances and energy saving products not regulated under the EPCA, such as a commercial range, commercial oven, insulation, or windows?

These are important factual and legal issues that should be addressed in this case to determine if the EPCA’s “concerning” language applies to the regulation of whole building GHG emissions that do not determine the energy efficiency or energy use of a covered product but instead regulate a building’s GHG emissions. Without doubt, the type and amount of energy use determine the GHG emission, but the GHG emission of a covered building is not solely determined by one or more EPCA regulated covered products in that building. The same is true of whole building energy efficiency performance standard used by the City of Denver.

Under the City of Denver’s performance standard, any commercial or multifamily building except for those with a demolition permit for the entire building and demolition has commenced on or before the compliance date must comply. The requirements for the City of Denver sets a specific energy total savings of 30% from all covered buildings by 2030 using annual energy reporting to demonstrate energy performance targets in 2024, 2027, and 2030 are achieved. The Ordinance uses Energy Use Intensity or “EUI” for each type of building regulated using known baselines. Alternatively, the requirement sets a 30% reduction below a buildings baseline EUI if there is inadequate baseline data. Site Energy Use Intensity is defined as:

A building’s weather normalized site energy use expressed as energy per square foot per year as a function of its size, normalized for weather and other characteristics that are significant drivers of energy performance as feasible with the reporting platform used. A building’s EUI is calculated by dividing the total energy consumed by the building in one year (measured in kBtu) by the total gross floor area of the building.

The Ordinance also applies to smaller commercial and multifamily covered buildings with floor areas of 5,000 to 24,999 square feet. For these smaller buildings, it sets an energy efficiency standard that requires either a lighting density of 90% (equal to all LED lighting), installation of solar panels, or purchase off-site solar that generates 20% of annual energy usage. This requirement is phased in by square footage over time:

- 15,001-24,999 sq. ft.: 12/31/25;

- 10,001-15,000 sq. ft.: 12/31/26; and

- 5,000-10,000 sq. ft.: 12/31/27.

The ordinance allows alternative compliance through adjusting the timing of compliance, a process to adjust the end goal due to a building use or inherent characteristic of the building, prescriptive options for smaller buildings, and compliance options for buildings where manufacturing and agricultural processes are the primary energy users. Finally, the ordinance implements electrification of end-uses for space heating, space cooling, and water heating at end of life of existing appliances. If natural gas is used again, it further requires an electrification retrofit feasibility report, sizing the equipment appropriately for the space or need served, and/or pressure testing of all natural gas piping.

Buildings are required to maintain the 2030 EUI indefinitely. There is a penalty of $0.30 per kBtu used beyond the interim targets and, beginning in 2031, a penalty of $0.05 per kBtu used beyond the 2030 target. The City is authorized to issue a penalty as high as $0.70 per year for each kBtu the building uses beyond the target amount but has stated that these lower penalties are what building owners can expect. The City can also assess a minimum annual penalty of $2000 for failure to comply with the energy reporting benchmarking requirement.

Because Denver used energy efficiency as its performance standard and not GHG emissions, it is more directly related to the “concerning” language of the EPCA. However, there is still a distinction to be considered between regulating a whole building’s energy efficiency performance and setting preempted specific energy efficiency and energy use standards. With out doubt, whole building energy efficiency performance extends beyond the covered products regulated under the EPCA. The next blog will discuss the only two cases besides the Berkeley opinion on point as well as other pending EPCA preemption lawsuits filed against the City of New York and State of New York.

Pingback: Blog # 3 on EPCA Litigation: What can the Limited Case Law Tells Us About Interpreting the EPCA? | The EPIC Energy Blog

Pingback: EPCA Preemption: What are its limits and How May it Harmonize with the Direct Regulation of Emissions from Appliances | The EPIC Energy Blog